Have diabetes?

Experiencing changes in vision, such as blurriness and eye floaters?

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the leading causes of vision loss around the world. Of an estimated 285 million people with diabetes mellitus worldwide, approximately one-third have signs of diabetic retinopathy.

Fortunately, there are several steps people with diabetes can take to prevent or minimize vision loss.

What Is Diabetic Retinopathy?

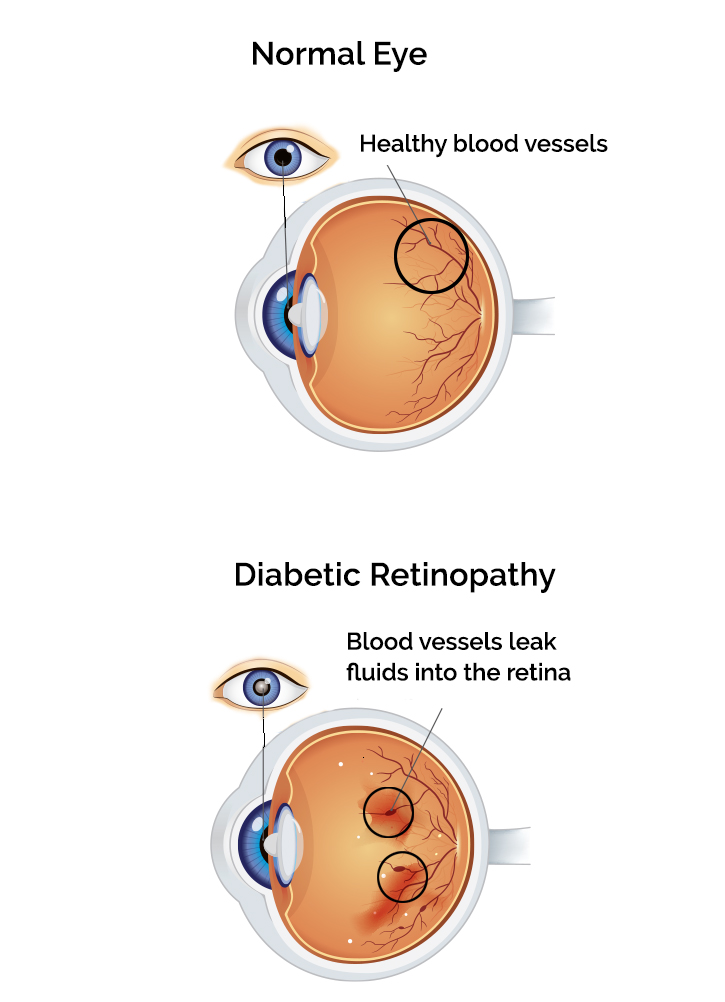

Diabetic retinopathy is an eye disease caused by high blood sugar levels that damage the small blood vessels clustered within your retina. This leads to swelling or fluid leakage and can result in vision loss and even blindness.

Diabetic retinopathy also raises the risk of retinal detachment and/or glaucoma.Because the early stages of diabetic retinopathy show no symptoms, many don't realize they have it until the disease has progressed.

If you have diabetes, you are at risk of developing diabetic retinopathy. To reduce your risk and protect your vision, schedule an eye exam with Southwest Vision Center today.What Are the Symptoms of Diabetic Retinopathy?

As mentioned above, the early phase of diabetic retinopathy typically shows no symptoms. This is why it's important to have routine eye exams (all the more so if you have diabetes), as your eye doctor can detect diabetic retinopathy in its earlier stages before symptoms become apparent.

- Blurred vision

- Floaters

- Double vision

- Near vision problems

- Seeing dark spots (scotomas)

- Difficulty seeing at night

What are the Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy?

Non-Proliferative Retinopathy (early stage):

This occurs when small bulges–or microaneurysms–form in blood vessels and can leak fluid into the retina.

Proliferative Retinopathy (later phase):

This refers to abnormal vessel growth and leakage in the retina. This triggers a variety of vision problems such as blurriness, reduced field of vision, and even blindness.

If you have diabetes, Southwest Vision Center in North Richland Hills offers diagnostic tests and treatment options to help preserve your vision. The earlier the diagnosis, the better the treatment outcome.

How Optometrists Diagnose Diabetic Retinopathy

-

Medical history

Your optometrist will ask about your medical history, including diabetes, as well as your family history of eye conditions.

-

Dilated pupil exam

Your optometrist will apply eye drops to dilate the pupils so they can see inside the eye and detect any issues.

-

Fluorescein angiography

This eye test uses a special dye and camera to look at blood flow in the retina and choroid.

-

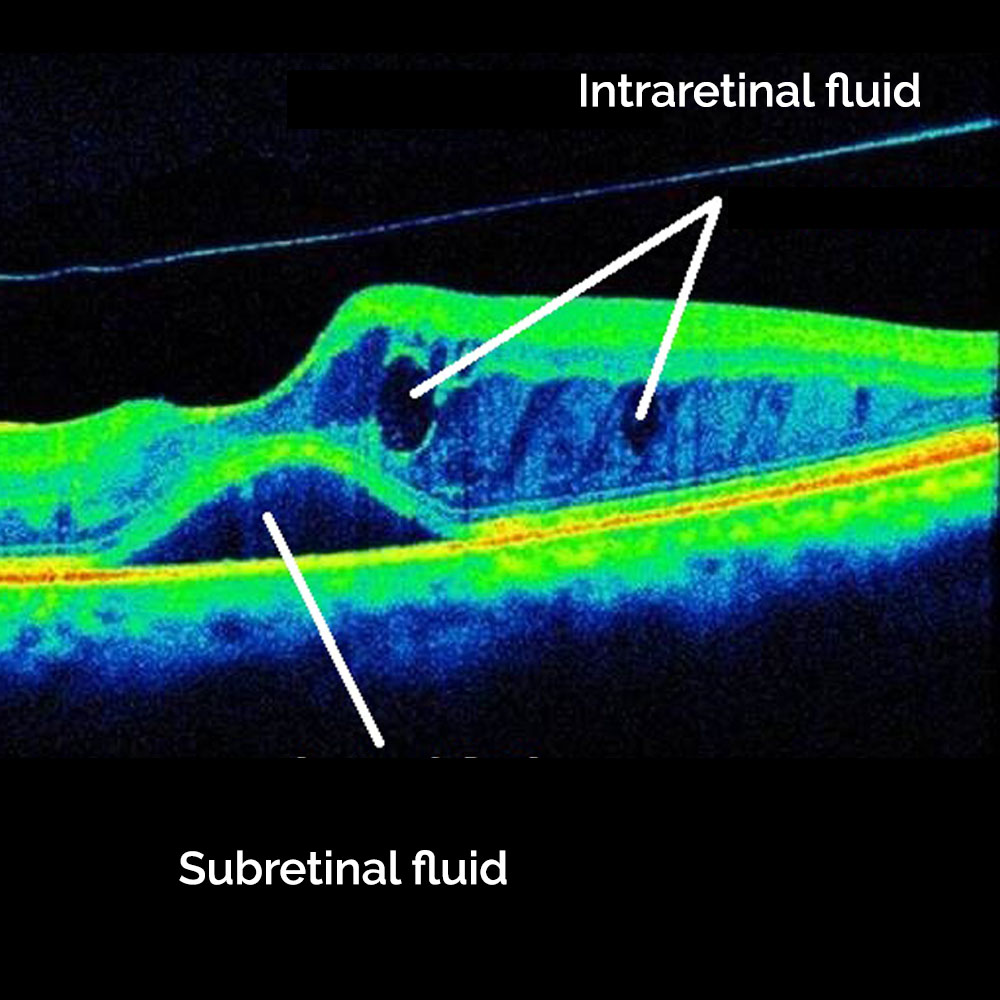

Optical coherence tomography

This imaging method shows a cross-section of the retina and can indicate whether vessels are leaking fluid into the retina.

Diabetic Retinopathy Diagnosis & Treatment in North Richland Hills

Meet our Eye Doctor

- Monday 7:00 am - 5:30 pm

- Tuesday 7:00 am - 5:30 pm

- Wednesday 7:00 am - 5:30 pm

- Thursday 7:00 am - 5:30 pm

- Friday 7:00 am - 12:00 pm

- Saturday Closed

- Sunday Closed

- VSP

- Medicare

- United Healthcare

- Aetna

- Spectera

- EyeMed

- Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield

- Blue Cross

How to Treat Diabetic Retinopathy

Treatment begins with managing blood sugar levels and diabetes. This means eating a healthy diet, increasing physical activity, and taking whatever diabetes medication has been prescribed.

Other treatments will depend on the stage or severity of the disease. If caught early, only blood sugar management may be necessary.

However, if you're in a more advanced stage of the diseases, treatment options may include:- Eye medications. Steroid and Anti-VEGF treatments can stop inflammation and prevent the formation of new blood vessels.

- Laser surgery. Reduces the proliferation of abnormal blood vessels and swelling in the retina.

- Vitrectomy. If you have proliferative diabetic retinopathy, you may need an eye surgery called vitrectomy. This procedure removes scar tissue, blood or fluid, and some of the vitreous gel so light rays can better focus on the retina.

Diabetic Retinopathy FAQs

As the name suggests, diabetes is the main risk factor for developing diabetic retinopathy. Be mindful of your family history of type 1, type 2 and gestational diabetes. If you have been diagnosed with diabetes, get an annual eye exam to detect potential problems early.

Other conditions such as high blood pressure and high cholesterol are also risk factors. Moreover, those of African or Hispanic descent have a higher risk of developing diabetic retinopathy.

There are a number of ways to preserve your vision and reduce the risk of vision and eye damage due to diabetic retinopathy.

- Visit your eye doctor for annual eye exams.

- Control your blood sugar levels.

- Maintain healthy cholesterol levels and blood pressure.

- Exercise regularly.

- Quit smoking.

The best thing you can do right now is to schedule your eye exam with Southwest Vision Center in North Richland Hills to ensure that everything is in check.

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the main causes of blindness among work-aged adults. It affects one in three people with diabetes and often goes unnoticed at first. Diagnosing and treating the condition early on can prevent severe vision loss.